Choosing your Bokken

Size, thickness, weight, wood, etc.

ed: This article was first published in French in 2015 on Seido's former blog.

If choosing one’s Bokken is an easy task for a beginner, it is a much harder endeavor for veterans in need of a tool able to support the focus of their work. The weight, length, species of wood but also the curvature and thickness of the Bokken play a determining role in the weapon’s behavior during practice. Let’s review all those components.

The reading of The choice of a specific Bokken for Aikido is highly recommended for a more practical pathway through 4 case studies.

Koryu Bokken

At Seido, we have decided to put forth the overall shape of the Bokken. Similar wood species are presented on the same page and wood species that significantly change the weapon’s characteristics are shown on a separate page.

Indeed, we think that the most important is to first pick the shape of the weapon. You will then choose the wood according to your expectations when it comes to wood species and resistance.

The length of the Bokken

One size fit all?

Considering that the length of a Katana or Iaito should fit the height of the practitioner, it is easy to think the same applies to a Bokken. Though it is indeed the case in some traditional Kenjutsu schools, in most arts it is very rarely the case and thus for two reasons. The first and most obvious one is that it is very difficult to tailor products to everyone individually. The other reason is related to the Bokken’s use’s nature that often requires an identical mirror distance. If two practitioners wield weapons of different lengths, the distance between the meeting/contact point of the weapons and the practitioners is therefore not the same, which de facto entails a change in technique, but working with weapons relies on specific Katas that need to be reproduced in an identical fashion by all practitioners.

Furthermore, in competitive arts such as Kendo, the length of the weapon can be a factor of advantage or disadvantage -as such, competitions carry specific rulings on the matter. In order to broadly adapt the size of the weapon to the practitioner’s height, length will tend to vary according to age and gender. Those norms are comprehensive, since a man can be shorter than a woman and still practice with a longer weapon. However during competitions, rules have to be put in place in order to level the playing field.

Note that in Kendo, the weapon used in competition is a Shinai (a lot more impact-resistant and less dangerous than a Bokken). The Bokken used for Kata will be the same size for everyone, since it’s about practicing Kata.

An Iaito is mostly used for Katas, too, so its size will fit the practitioner's height. The reasoning is simple: some cutting techniques and, more importantly, the unsheathing of the sword from the saya (scabbard) cannot be done with a sword too long.

Or tailored length?

Despite a mostly harmonized length for each art, some Koryu do adapt the length of the weapons to the practitioner.

In general, those schools use the Bokken either as a full-blown weapon or as in a battlefield bout rather than in a Kata (duel). Those Koryu are generally older than Kata-oriented schools, less focused on duels (Kata) than on a battlefield usage, and have overall been much less influenced by the Edo period, the era of peace. One of those schools, for example, is the Jigen Ryu school, established during the 16th century and famous for its emphasis on the importance of the first strike.

That being said, a sword length tailored to the user can very well be considered when practicing Aikido, Jodo, or some other specific schools. For example in the case of a specific study, such as breaking the fixed distances principle and by doing so drive the student to better their adaptability to various situations- once the Kata are mastered.

In the end the answer is quite simple: if your teacher offers a Bokken suited to your size, they probably have their reasons and his work is tailored accordingly. If you have reached a certain level of practice and wish to acquire skills other than those acquired through the sole practice of Kata, then a Bokken of a suited length is warranted (mostly longer, as Bokken tend to be relatively short for western practitioners).

The various lengths of classic and stylized Bokken (Koryu)

| Model | Total length | Blade length | Tsuka length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chuto (kid) | 90.5 cm | 68 cm | 22.5 cm |

| Standard/Deluxe Bokken | 101.5 cm | 75.5 cm | 26 cm |

| Iwama Bokken | 103 cm | 76 cm | 27 cm |

| Iwama Takemusu Bokken | 101.5 cm | 75 cm | 26.5 cm |

| Niten Ichi Ryu Bokken | 101.5 cm | 76 cm | 25.5 cm |

| Yagyu Ryu Bokken | 101.5 cm | 75.5 cm | 26 cm |

| Yagyu Shinkage Ryu Bokken | 101.5 cm | 73.5 cm | 28 cm |

| Shingake Jiki Bokken (thin) | 101.5 cm | 77 cm | 24.5 cm |

| Shingake Jiki Bokken (heavy) | 101.5 cm | 75.5 cm | 26 cm |

| Kashima Shinto Ryu Bokken | 106 cm | 78 cm | 28 cm |

| Kashima Shin Ryu Bokken | 104.5 cm | 78 cm | 26.5 cm |

| Katori Shinto Ryu Bokken | 97 cm | 70 cm | 27 cm |

| Shinto Ryu Bokken | 101.5 cm | 77.5 cm | 24 cm |

| Jigen Ryu Bokken* | 101.5 cm | 75.5 cm | 26 cm |

| Hokushin Itto Ryu Bokken | 106 cm | 76 cm | 30 cm |

| Itto Ryu Bokken | 98 cm | 73.5 cm | 24.5 cm |

| Keishi Ryu Bokken | 101.5 cm | 73 cm | 28.5 cm |

*Length might vary depending on the user, used in "standard" 101.5 cm until a more suited length is found.

Please note that the blade/tsuka length ratio can vary slightly depending on the manufacturer. This is due to the fact that numerous schools are split into regional sub-groups that sometimes have their own small peculiarities and order from various workshops.

The weapon’s weight

The thickness and weight of the weapon play a major role in its usage. It could even be considered its most important feature, more important even than its length.

It is indeed harder to be precise with a light Bokken than a heavy one. A lighter model allows for more finesse, all in precision and swiftness.

In contrast, and provided the required physical training (tanren), a thick Bokken is easier to wield with precision, it is therefore essential to have the required strength to wield it properly.

Thus, young masters are often seen starting off with very thick Bokken or practicing a lot of Suburi using a Suburito. They then gradually move toward thinner models for more precise work. That was the case of Aikido founder Morihei Ueshiba, who had worked for a long time with a thick and heavy Bokken (similar to the current Iwama Ryu model) and then switched to a thinner model for the last 20 years of his life (that seemed to be a Yagyu Ryu or Jiki Shinkage Ryu Naginata Yo model).

The thickness of the Bokken

Though each model originally comes with a specific thickness, the choice of thickness during the design of the weapon is used to adjust the average weight of the Bokken and its balance. Wood has a non-negligible impact on the Bokken’s weight, but the average weight of white oak can significantly vary depending on the selected wood.

The thickness mentioned is usually the thickness at the base of the tsuka (handle) (tsukagashira, or tsukajiri), and this thickness will determine the overall thickness of the weapon (related to the Mine, see following chapters). However, there are some models for whom the blade’s thickness is determined independently of the rest of the weapon. But those models are very rare.

Thickness also has a very important influence on the tenouchi or "grip" on the Bokken. Indeed, the thicker the tsuka (the heavier the Bokken), the more strength will be required to hold it. Conversely, a very thin Bokken will be harder to wield.

The various thicknesses of classic and stylized Bokken (Koryu)

| Model | Tsuka thickness | Weight in white oak |

|---|---|---|

| Chuto (kid) | 35 x 25 mm | 500 g |

| Standard/Deluxe Bokken | 37 x 26 mm | 600 g |

| Iwama Bokken | 38 x 28 mm | 700 g |

| Iwama Takemusu Bokken | 39 x 29 mm | 750 g |

| Niten Ichi Ryu Bokken | 33 x 20 mm | 330 g |

| Yagyu Ryu Bokken | 30 x 22 mm | 400 g |

| Yagyu Shinkage Ryu Bokken | 34 x 24 mm | 550 g |

| Jiki Shinkage Bokken (thin) | 29 x 21 mm | 360 g |

| Jiki Shinkage Ryu Bokken (heavy) | 44 x 39 mm | 1300 g |

| Kashima Shinto Ryu Bokken | 38 x 30 mm | 880 g |

| Kashima Shin Ryu Bokken | 38 x 30 mm | 1,000 g (with wooden tsuba) |

| Katori Shinto Ryu Bokken | 38 x 27 mm | 620 g |

| Shinto Ryu Bokken* | Thin: 34 x 22 mm Thick: 36 x 24 mm |

500 g 580 g |

| Jigen Ryu Bokken | 40 x 29 mm | 740 g |

| Hokushin Itto Ryu Bokken | 39 x 29 mm | 900 g |

| Itto Ryu Bokken | 41 x 31 mm | 680 g |

| Keishi Ryu Bokken | 40 x 30 mm | 780 g |

*There is a model said "light", mostly aimed for women, and one said "heavy" for men.

Beware, weights vary widely depending on the wood being used and the time of the year. Expect a 10 to 15% difference from the above values.

We then tend to classify those weapons into 4 categories: thin, standard, thick and extra-thick.

Curvature, amplitude and position

The curvature has a strong influence on the balance and handling of a Bokken. Moreover, on a Bokken just as on a Katana, the main role of curvature is to cushion the force and significantly strengthen the weapon’s resistance to impact. In the case of a Katana, it also gives a better cutting angle, making slicing easier.

Most practitioners, even at a confirmed level, wouldn’t be able to differentiate between two classical Bokken from different workshops, which will have a slightly offset curvature focal point and an amplitude difference of 1 to 2 mm. Curvature has little impact here.

However, many models have very little curvature and a few of them have very wide ones. A light curvature makes strikes and movements more precise and more direct overall. It is actually the reason why many schools offering Kata Bokken vs Jo or Bokken vs Naginata adopt lighter and less curved (perhaps even mostly straight) weapons, in order to compensate for the gap between weapon length with speed and precision.

Inversely, some schools such as the Kashima Shin Ryu tend to focus on power and will offer heavy and straight swords in order to push the balance toward the Kissaki (tip) as much as possible. Doing so, they tend to feel like a Katana.

A "common" sori of about 25mm allows a good middle ground between handling, balance and impact resistance, making it the obvious choice for a "standard" Bokken.

The curvature position, koshi sori (close to the tsuka), Kyo sori (centered) or saki sori (at the tip) will influence two characteristics: power and cutting angle. With a sori that is close to the tip, the monouchi (the upper third of the weapon used for cutting) is shorter and cutting will require more precision. A centered sori is more akin to what can be seen on a wide amount of Katana, giving a true 1/3 of the blade for cutting, and a koshi sori will slightly lengthen the monouchi of a few more centimeters.

Balance is also slightly changed. The closer the sori is to the tip, the more the balance will shift toward it.

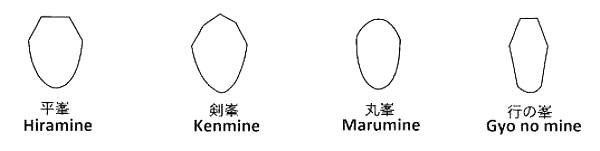

The mine is the upper spine that determines the shape of the blade

Contrary to what one might think at first glance, it is one of the most impacting elements on a Bokken’s weight and balance.

Indeed, while Hiramine and Kenmine finish are similar, Marumine and Gyo no mine finish influence the blade’s thickness heavily.

- Hiramine : classic.

- Kenmine : classic, but with a little more weight added to the blade.

- Marumine : more weight on the upper part of the blade, but the blade is overall thinner and balance is shifted toward the kissaki.

- Gyo no mine : makes the blade tremendously thinner and is mostly used for very light Bokken such as Miyamoto Musashi’s Niten Ichi Ryu.

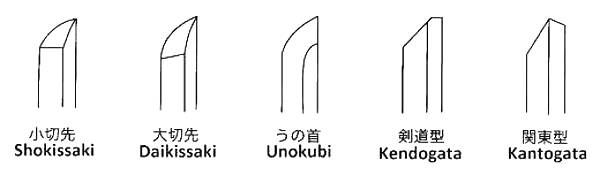

The Kissaki, the finish of the tip

Influence is minimal, but the Kissaki’s finish allows a slight offset of the weapon’s balance without significant change to its weight.

- Sho kissaki : classic balance.

- Dai kissaki : shifts balance toward the tsuka (change is non-existant as generally, daikissaki weapons are designed with a kenmine finish that adds a slight overweight to the weapon).

- Unokubi : identical to Shokissaki in terms of balance.

- Kendogata : beveled on the blade side, straight on the mine side. This allows to significantly lighten the Kissaki and switch the balance to the tsuka.

- Kantogata : beveled on the entire blade’s thickness, for a mostly similar result to the Kendogata.

- Iwama ryu (straight cut) : in contrast to the previous cuts, this one adds a significant weight to the tip, and switches balance toward the kissaki.

You now understand why a standard Bokken with Hiramine finish has a smaller Kissaki, while a deluxe Bokken with Kemine finish has a longer one. One compensate the other, and balance on a standard Bokken is mostly identical to a said deluxe Bokken.

Presence of a groove, or bo-hi

The groove, borrowed from the katana’s groove, aside from the sound it generates on impact, is very significant in two ways. It makes the weapon a lot lighter, and moves balance a lot closer to the tsuka.

"But then why move balance toward the tsuka for Iaido Bokken, since Iai is focused on practicing with a real sword?", you might ask.

The answer is rather simple: Kenjutsu mostly focuses on sword fighting, whether it’s with a Bokken or a Katana. Iai, on the other hand, focuses on Kata, and Iaito just like Bokken are strongly balanced on the tsuka in order to facilitate the weapon’s handling. Some schools of course offer other kinds of studies in order to steer toward cutting at a later stage.

And finally, in which wood species?

First things first: please read our detailed article about wood species, as we won’t cover the entire topic here.

Next up: a wood that is solid, resilient, and gets etched without shattering... In short, Japanese oak, white or red. The wood is the weapon, and makes up to 80% of the work - that is weight, balance, energy transmission, vibration absorption, etc. Oak also has the huge advantage of showing signs of weakness before shattering, it wears down progressively which allows the detection of possible problems and discarding a potentially dangerous weapon.

So the Japanese wood that combines all those characteristics the best is oak, or Quercus acutissima by its scientific name, which is the same species for both red and white variants (If we’re being honest here, Hon Biwa or loquat is overall better, but who would recommend a 700€ Bokken for contact practice?).

The quality of wood is measured through 4 factors: its impact resistance, density/gravity, consistency over time, and behavior in regard to impact and destruction.

A wood being very strong to impacts doesn’t necessarily means it would be a good fit to make a Bokken, as it also requires a good enough density. Which allows for a satisfying weight, not too heavy and with good long term behavior. And more importantly, relatively long and flexible fibers so that the Bokken would shatter along its length in a safe way in case it would break.

Camellia, Buna or Isu no Ki come next with significantly worse characteristics when it comes to strength to impact and consistency over time. Camellia makes for beautiful weapons, for a gift or for practice of contact-less Kata. Buna and Isu no Ki are good wood species, very light, for Kata also.

Murasaki Kokutan (purple ebony), Sunuke, Asian ebony and African ebony in order of density (weight) are heavy, massive, beautiful and ideals for Suburi, but very poor when it comes to impact resistance. Their density makes them feel very sturdy at first, but when their resistance levels are tested, unlike oak that tends to bend and keep absorbing impacts before ("progressively") breaking, massive woods explode in a relatively dangerous fashion. On the other hand, they stay consistent over time and can keep their integrity for decades. Given their weight and their beauty/rarity (cost), they make for excellent gifts and Suburi-oriented Bokken.

And finally, please note that we highly advise against contact use between Bokken made of woods that widely differ in density. Indeed, a Bokken in Sunuke, even on light impact, will immediately and deeply damage an oak Bokken, and doing so destroy some fibers. This will destabilize the impacted area of the wood in the medium-term future (accelerated aging). A Bokken made of African ebony could even completely destroy a white oak Bokken in only a few strikes...

What about me? What should I get?

What is important to understand is that a Bokken is a specific tool for a specific job. The same way you would drive a nail with a hammer and not with a mace, you wouldn’t practice Iai with a Bokken Iwama ryu, or Kashima with a Bokken Yagyu Ryu.

Long story short, if your school, like the near-majority of Kenjutsu schools, offers a specific weapon, then get yourself the model your school recommends! (You won’t be permitted to practice with any other model anyway).

If you practice Iaido, you then have two choices. Either a classic Bokken, with or without groove. For beginners, a regular Bokken is enough, though it could quickly get heavy and hard to handle. It is then generally better to go for a Bokken with a groove, with which you will be more accurate and get less tired.

If you study Aikido (which the exception of the Iwama school, since they make use of their own model) or any other art that leaves you relatively free in your choice of Bokken, it gets more difficult, but let’s keep it simple:

Are you a beginner? Then pick a relatively light and not too brittle Bokken (in case of an accident), for example in red Oak. If you are more on the frail side physically and you know for sure there will be no full-contact practice in your dojo, you can even consider a weapon made of Isu no Ki. But whatever your choice, start with a classic model! Starting with a sword that is too light won’t help with strengthening your body, and a sword that is too heavy will cause corporal damage in the short/mid-term.

You have been practicing for a few years already: look at what your more experienced fellow dojo members are using. Analyze the kind of work you’re doing: is it subtle and precise work, focused on timing? Or a more static work, more focused on power? In the first case, a lighter Bokken would be the best choice. In the latter, a heavier Bokken (but not too heavy, as weight should be raised gradually, in order to avoid traumas, most notably tendinitis).

You have been practicing for 10 or even 20 years? You then most likely know already what you are expecting of your practice, what are your research angles... All the above points should help you choose the most suited weapon for your needs.

And in any case if you have doubts, do not hesitate to contact us, via comments or through email, and we will help you make the right choice to the best of our ability.

Frequently asked questions:

Would it be possible to make a sword with balance and weight similar to a Katana?

To put it simply: no. A sword has a steel blade, much more dense and heavier than wood. Considering that its tsuka is made of wood, a sword has to be balanced at the tip.

Furthermore, what sword? With or without groove? With which curvature? What balance? Shinken, the cutting swords, are tailored-made to each user, such that there is nothing specific to "imitate".

Which Bokken is the sturdiest for full-contact practice?

Objectively... A red or white oak Bokken will be the strongest. But the question is worrisome... A Bokken is a tool for martial art practice. By hitting strong enough, you can destroy any weapon, whether it’s made of wood, iron, steel, or even titanium. Each art teaches a specific usage and, in most cases, the weapons used are fitted to the type of practice on offer.

What warranties are your weapons covered by?

None other than they are straight.

Do you know of any store or any brand that would offer warranty coverage on a product intended to break eventually?

Bokken are made of wood. Some are sturdier than others, but wood is an organic material. Even without visible defect, it can have structural ones, invisible and impossible to detect.

And wood ages. It dries up, and progressively loses its mechanical features (even more if badly maintained). This can take a few years for a poor quality Bokken, but 10 to 20 years for a more consistent wood. But whatever the wood; it’ll always end up wearing, losing its virtues and eventually, break.

Of course, a good "Made in Japan" Bokken has a lot less chance to show defects or break than a substandard one made in China or Taiwan...

1 comment - Choosing a Bokken - Size, thickness, weight, wood, etc.

Im thinking of getting a bokuto made for me i chose the Classic as length and grip width,a Hiramine grip and a Unokubi tip.

But the problem is i don’t know how wide should the blade be(like the blade’s dimensions) nor how curvy it should be.

Any help would be appreciated

Thank you<3