An Interview with Hoshi Norio

Kendo Kyoshi 7-Dan - Tokyo Police

ed: This article was first published in French in 2012 on Seido's former blog.

Hoshi-sensei is a close relative to Seido Founder. He works with us as an adviser, and tests and controls many of our products. I had many opportunities to interview him in the past, but now that I have trained and studied under him, I feel that I understand the man and the Budoka much better. Now is the right time to finally sit with him and talk about martial arts.

Hoshi Norio is one of those Budoka that you never hear about outside Japan. Reserved, simple, hard-working, away from the internationalisation of martial arts... He is nonetheless an extraordinary Kendoka and police officer. He started Kendo at age 10, in a provincial junior High school’s club, aiming from the very beginning to become a professional Kendo teacher.

Various encounters with teachers from different horizons gradually impacted his "sports" vision of Kendo, ultimately reshaping it into a deep knowledge of the Spirit of Budo. He would also understand very early on that, above all, he wanted to be of service to others. He thus decided to attend the police academy and soon started his career as a low-rank officer. His tenacity however, his commitment and his Budoka spirit would eventually take him much further. While practicing and working hard every day, he decided to take evening courses at the academy, and became a divisional commissioner, the highest rank that one can achieve without having a law degree priorly.

What makes Hoshi Norio an exceptional man is not only his professional career, but also his Budo career. Like many police officers, he is also a dedicated Taihojutsu practitioner (8-dan), and he enjoys studying Iaido and has reached the 3rd Dan in that discipline. Taihojutsu puts together self-defence and arresting techniques, and is widely practiced by Japanese law enforcement officers and by the military. His vision of Budo, and more particularly of Kendo is very simple: Kendo does not stop at the doors of the Dojo, it should be embodied in our everyday life. Kendo manifest itself in the sweat during practice.

Although he holds the title of Kyoshi, he is not a "teacher" in a Western sense. He has not developed any theory, and he rarely uses words to correct anything. On the contrary, he shows Kendo only from the postures and the movements of his body. Hoshi-sensei is the oldest Japanese competitor to have participated in the Tokyo Police Tournament. His last fight was in 2010, at 59, ending in Hikiwake (tie).

Hoshi-sensei - Tokyo Police Annual Kendo Tournament (2010)

Seido: Hello Sensei, thank you for this interview. First, could you tell us when and why you started Kendo?

Norio Hoshi: No, thank you! I think this is actually the first time someone is interviewing me about Kendo.

I started Kendo when I was 10. Today, it might sound early, but in those days 10 was rather late. It was at the Kendo club of my junior high school, in a very remote area. The atmosphere was good, and I needed to get my energy out. My brother was already practicing Kendo, so I signed up.Seido: This is a very classic story in Japan... When did you realise that Kendo was more than just a mere physical activity? How did the shift happen?

Norio Hoshi: A few years later, in high school. My teacher then was quite special, he had a unique aura, both during the class and outside the Dojo. His Kendo was not only technical, combative, it was also clear, precise, and firmly rooted in Reigi (etiquette). His Reigi was not an empty shell, like we often see, it had meaning which resonated in his daily life.

This is when I understood that Budo was a way of life, imbued with values such as honesty, kindness, but also vigilance and intransigence. In a few months, Kendo transformed me, and I stopped doing stupid childish things. I started to respect things, plants, animals, people, and my vision of life changed. It was then that I decided to become a police officer. I wanted everyone to understand what I understood, and I thought, with a bit of idealism, that law enforcement would be the best way to communicate these things.Seido: I have heard many times that when you were transferred to Tokyo, you arrived there with only your Shinai and your Bogu… True story?

Norio Hoshi: Yes, true story! I didn't have much money, and I only thought about Kendo. I took the only things that were important to me: my equipment. I went straight to the police precinct I was assigned to. When they saw me at the door, Bogu in hand, my supervisors sent me to the Dojo to train (note: all Japanese police stations have a Dojo). Or maybe they wanted to test me… I think it went well, because I received a lot of help to settle in Tokyo.Seido: Why did you so relentlessly wanted to reach the highest possible rank, both in Kendo and in the police?

Norio Hoshi: Rank is only a consequence! As a Kendo student, I practiced with all my heart, every day, until I reached 3-Dan. I then did the same as a teacher in the several police precincts where I worked (note: in Japan, a commissioner assignment changes approximately every two years).

I trained the police Kendo teams, and I absolutely wanted to take them to the top. I did a lot of competitions, almost a hundred tournaments in total. I was good enough and I quickly rose in ranks. However I felt one day that competition was taking over: I thus decided to practice Iaido, in order to refocus my mind on Budo.

(note: Hoshi-senseï did not talk about it, but I was able to consult his competition charts: 89% victory, 5% draw, 6% defeat, spanning over almost 40 years of career. It is one of the best scores ever in Tokyo police).Seido: I actually know your results, it's impressive. What about your rank in the police then?

Norio Hoshi: This is a little more complex. On one hand, my results as Kendoka had allowed me to stand out and to be noticed by my hierarchy. On the other hand, I think that a very righteous Budoka life inspired confidence. Beyond intellectual skills or experience, my supervisors were looking for honest, upright people to fill in the positions of responsibility.

Trust was probably the most important thing. I passed all my exams, often as a valedictorian, but I was certainly not the best. In the end, I became a divisional commissioner for the Kanto region. Regular Kendo practice and victories in competition are proofs that you are robust, physically fit. Even if strategy matters in kendo, when one is young, it is all about the body.

I think I also needed to find balance and prove to myself that my mind was as sharp as my body, that's why I always enjoyed my lessons at the police academy, even well after turning 30.Seido: I suppose you were with your subordinates like you are with your students? Very fatherly?

Norio Hoshi: I don't like that term very much. I'm neither their father nor even their family. But indeed, I have a certain amount of experience and I want them to benefit from it. However, I am not particularly good with communication. Maybe my attitude could be described as paternalistic: severe, but benevolent.

Over time, things changed though. For the past ten years, I have seen my colleagues more as friends.

Finally, if there are differences between age 30 and 40, they feel less significant between 40 and 50, or 50 and 60. I think I was one of the few commissioners who organised dinners at home with half the police precinct! (laughs) We had great fun!Seido: You worked mainly on traffic and civil affairs. You were not interested with felony or crime?

Norio Hoshi: To be honest, I don't know! Japan is a relatively calm and safe country. There are few murders, few drugs problems, few thefts... I'm not sure I would have had the courage to see the worst sides of men, every day.

My job was mainly about fixing incivility, rather than dealing with crazy guys. Catching a criminal in order to punish him didn't seem like a job for me. so I stayed where a real work of prevention and education was needed, rather than focusing on repression.

Preparation time (meditation) before the first Shiai

Seido: Let's go back to martial arts! You are also a Taihojutsu 8-dan. In what context did you study this rather unknown martial system?

Norio Hoshi: This is a delicate subject, on several levels.

First of all, I'm not sure I deserve this 8-dan! Taihojutsu is very much linked to the police as a profession, and the highest grades were certainly awarded to me with kindness, in relation to my police rank.

In fact Taihojutsu practice is more or less compulsory for police officers; less indeed at my level. In all honesty, I haven’t trained much for the past 10 years. (laughs)Seido: About Kendo now. In 2010, you were the oldest competitor in the Japanese police, is that correct? (see video below).

Norio Hoshi: Yes indeed! I even got a certificate for that (laughs). I didn't win a single Shiai, though! (note: he didn't lose either)..Seido: Why did you continue competing for so long (until 59), when most officers stop when they reach their 40’s?

Norio Hoshi: For several reasons. I was asked to, in fact! And since I’ve always had good relationships with my students, I could not refuse them.

From a more personal point of view, I always thought that Kendo (Budo) should be practiced until the very end. Today, at 61, I would probably not be able to win many Shiai anymore, and I would get injuries often.

Anyway, I am retired now, I am no longer a law enforcement officer, so the question does not come up anymore. I can no longer participate.Hoshi Sensei's last Shiai was during the annual Tokyo police competition (86th edition) in 2010. The bout ended in "Hikiwake" (tie).

Seido: I have seen you teach on many occasions. You do not speak much, you correct very little, but your students are good. What is your recipe?

Norio Hoshi: I don't have any! I practice with all my heart, facing all my students one after the other. It is up to them to ask questions, it is up to them to see what is working and what is not. After the 3rd Dan, everyone should be capable of understanding their own mistakes.

Those who do not want to question themselves and change their practice behaviours will never reach the top. Today, their physical abilities, their speed, their sight or something else may give them victory, but they will sooner than later be overwhelmed by technically proficient opponents.Seido: Now that you are retired, what do you plan to do?

Norio Hoshi: I have a second job in the administration. It is not really exciting, but I have fewer responsibilities and a lot more time. I now teach Kendo to children. It is a difficult exercise for me, I am not used to giving advice to people that young. And as you know I practice at your home Dojo regularly. Speaking of which, thank you for offering me a space for practice. The Dojo is a bit low-ceiling though (laughs). (note: Seido's former building had a small traditional 12-tatami Dojo).

If you ask me if I plan to teach more from now or organise seminars, then the answer is no. I agreed to hold a seminar in France (see below) because you asked me to, and because you assured me there would be a good atmosphere… But I am not good at teaching, honestly. If someone asks to train with me however, I mean simply to practice with me, then it will be with great pleasure.Seido: We could talk for hours, but let’s finish with this question: “What would you recommend to all Budoka? Something you understood along the way and you would like to tell them?

Norio Hoshi: I would tell them that having exemplary behaviours outside the Dojo is essential for a Budoka. Winning a Shiai or a tournament is of course satisfying, but the satisfaction is ephemeral. Any sport can bring you those emotions. But being a Budoka is something else: it is about drawing life lessons from your practice that allow you to better yourself, and interact better with yourself and with others.In the Dojo, (but it's also valid in life), I would simply tell them “Do not be afraid”. Overcoming fear is 90% of the martial way. Kendo, Aikido, Judo, Karate… everything is in the minds of practitioners. Only with a just mind can techniques be expressed. If you are afraid to be hit, to lose, to disappoint, whatever this fear is, it will prevent you from controlling the timing, the distance and the power necessary to perform the Waza. Budoka's biggest enemy is fear!

Seido: Thank you Sensei!

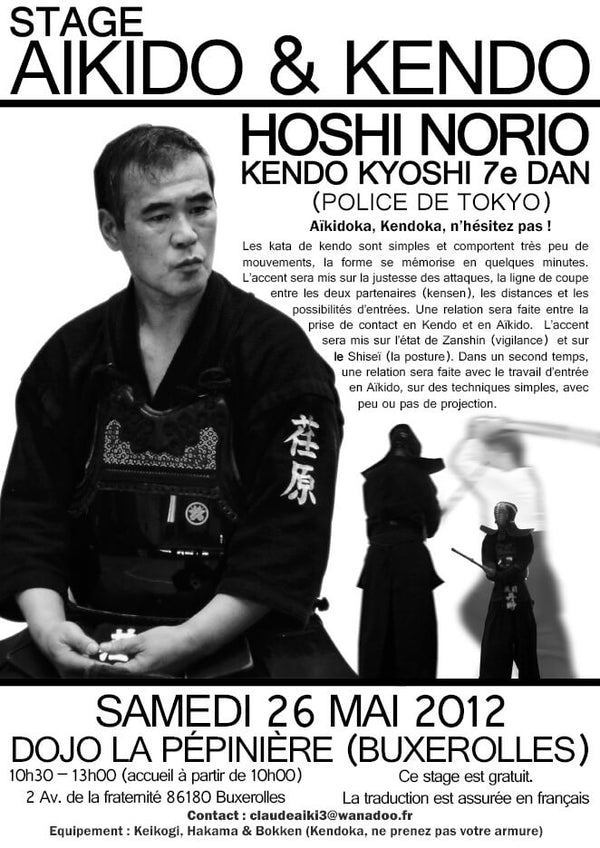

Seminar in Poitiers (France). May 26, 2012 — Kendo & Aikido:

Hoshi Norio Sensei will hold a seminar on Saturday May 26, 2012 in Poitiers. He will be assisted by Seido’s very own Jordy Delage. The aim of this seminar is to convey the universal elements of Budo by working transversally on Kendo and Aikido techniques. French Translation will be provided by the Seido staff. The seminar is free.

Seminar poster

This article gathers elements from the main interview but also from several discussions in the Dojo, weapons in hand. Some parts were not transcribed from recordings, but the article was read and approved by Hoshi-sensei prior release.

Reproduction of all or part of this article (with the exception of the seminar poster) is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of SeidoShop or Hoshi Norio.

1 comment - An Interview with Hoshi Norio

Thank you for that article and perspective. Very honest man about his motivations in police work. I do believe that budo helps in dealing with the felons and “crazy guys,” too, even in US society, which is far more dangerous and where things are much more precarious now. Would that every precinct here had a dojo!