Ink Sticks

Everything you need to know

ed: This article was originally published on the former website of Fuh-Mi (a Japanese calligrapher who mainly works in the field of contemporary art and who offers many works on our website).

It may seem strange to those unfamiliar with calligraphy, but ink is traditionally sold as solid sticks rather than liquid, and each calligrapher must grind down his ink sticks with water on a specific stone called suzuri, before he can start brushing.

The majority of Japan's ink is produced in the Nara region, where renowned manufacturers such as Kobaien, which was founded in 1577, still operate.

All about ink sticks

Ink sticks exist in many different shapes and sizes, but they all follow the Cho weight system: 1 cho (1丁) = 15g. As a result, a 5-cho ink stick, regardless of shape, will weigh 75g, a 10-cho 150g, and so on. The Japanese system differs from the Chinese system, where 1 cho (or 1-kin, if we use the original Chinese character) equals 500g, and following measurements are fractions of that base weight: 2 cho = 500 x 1/2 = 250g; 4 cho = 500 x 1/4 = 125g, and so on.

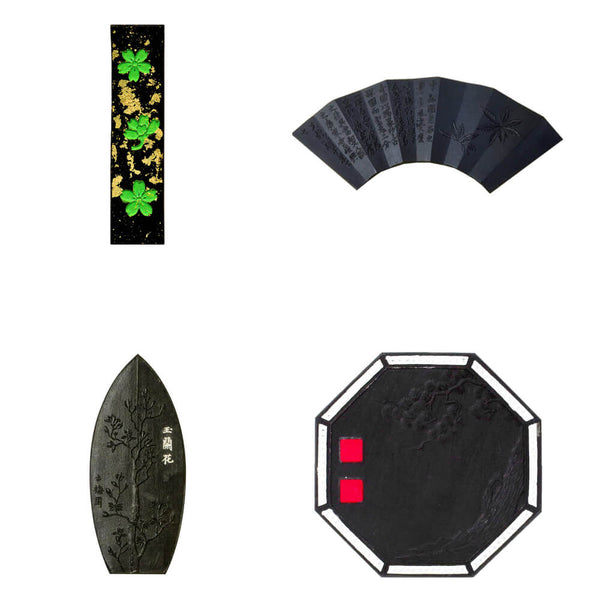

Ink sticks generally come as parallelepipeds, but they can be in fact of many shapes, like round, oval, octogonal, etc.

Different ink stick shapes made by Kobaien in Nara.

Ink sticks are made by mixing soot with nikawa, an organic binder made primarily from buffalo hide (sometimes horse's or other animals). Because nikawa has a rather foul odour, manufacturers add other ingredients to the blend which work as preservatives and, more importantly, improve the scent.

The soot mixture is then compacted and moulded, trimmed, and air-dried for several months before being painted with the brand name, product name, or traditional drawings such as pine trees, bamboo, and so on.

When brushed, the ink's behavior is affected by the soot / nikawa ratio. The ink will be heavier (stickier) if there is more nikawa in the mix. A calligraphy ink stick made with a lot of nikawa will also create a hazy effect on the calligraphy. A stick with less nikawa, on the other hand, produces a light texture ink that flows smoothly over the paper and produces crisper calligraphy.

In comparison to Chinese ink sticks, Japanese ink generally tends to have more nikawa in the blend.

Ink, old and new

High-quality ink sticks can be kept for decades, much like wine aging gently in an old Bordeaux chateau. The nikawa loses some of its binding strength as time goes on, and the stick develops a subtle patina, resulting in a smooth ink with unique hues. Aged ink is called koboku.

Some ink sticks, particularly koboku, can be extremely expensive, occasionally approaching the value of gold!

The Kōfuku-ji Nitaibō Koshiki-sumi, or "ancient ink type from the Kōfuku-ji temple," made in collaboration with Kobaien, is one of the most expensive inks still produced in Japan (if not the costliest): more than 700 USD for 20g!

It is produced from a rare sort of nikawa known as akyō (阿膠), which is derived from donkey hide, and is cast in a particular iron mould devised more than 6 centuries ago during the Muromachi period.

Ink has a long and fascinating tradition, with a history extending back thousands of years. It was first imported from China, like many other cultural assets, but Japanese ink culture grew and diversified from its origins to become something unique.

2 comments - Ink Sticks

What is the source that Chinese inksticks have less binding that Japanese? In practice I have never seen such thing.

Do you know of a good way to appraise 60 year old inksticks? Bought in Japan or Taiwan in the 1970s. Thank you!